Still catching up on these! This newsletter will, though (for another day at least) bring us up to date. The podcast has been barreling along: I hope that by now you’ll have listened to my conversation with the utterly charming Willard Spiegelman about a fascinating poet, Amy Clampitt, and her wonderful “Losing Track of Language.” (If that link doesn’t get you the whole poem, try this one.) If you haven’t yet, you can find the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts.

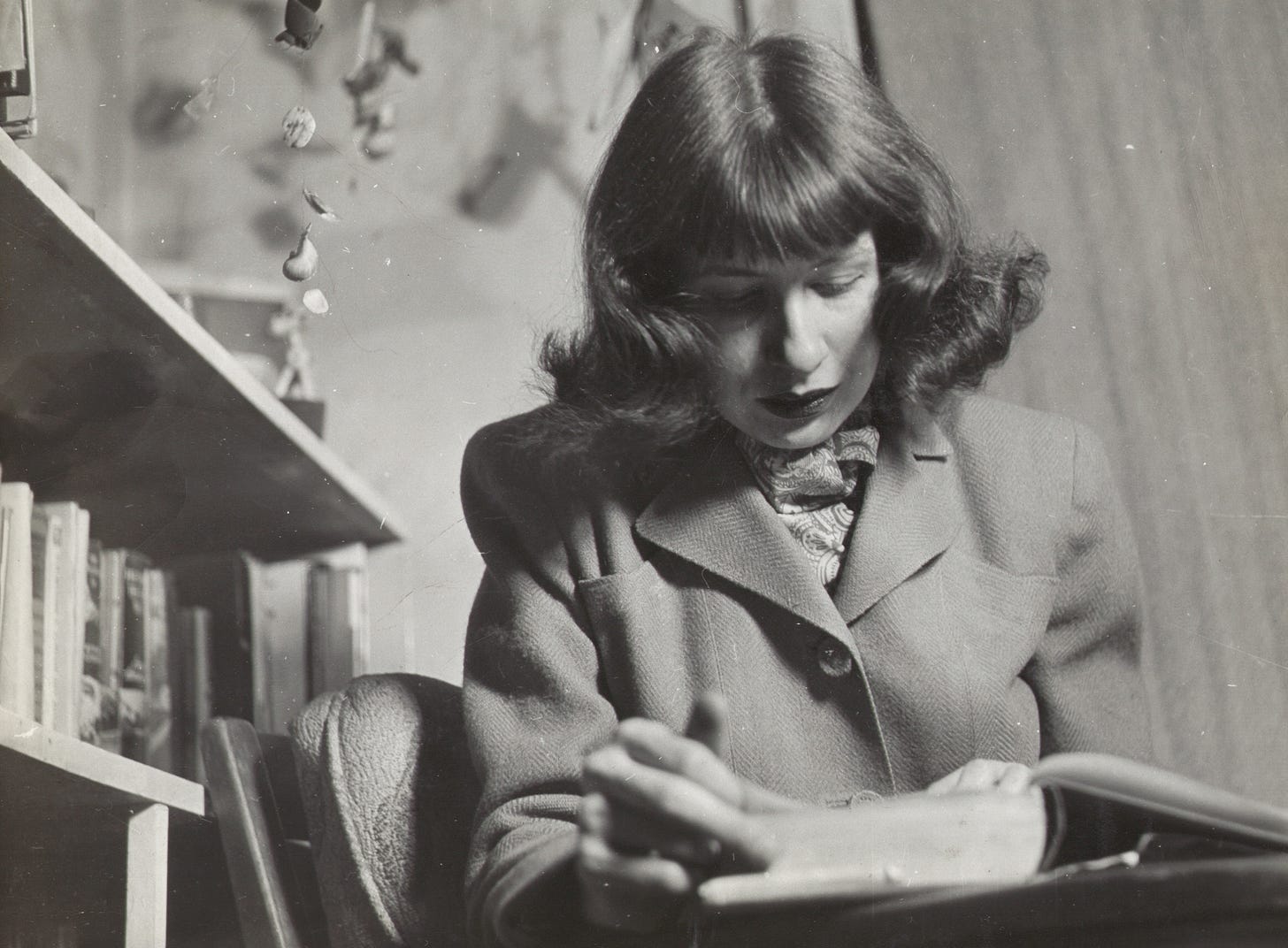

Willard calls Amy Clampitt “the patron saint of late bloomers”; she didn’t publish her first poem—in The New Yorker, no less—until she was 58 years old. That was in 1978, and what followed thereafter was a great rush of poems, most of them also first published in The New Yorker.

“Losing Track of Language” redescribes a train journey Clampitt took in the early 1950s (and which she tried, back then, to describe in prose). Thirty or so years later, that memory takes shape as a poem:

Willard points out, early in our conversation, that this poem shares some features with another great poem set on public transportation (perhaps my favorite poem ever), Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Moose.” But whereas for Bishop the poem arises out of a relatively silent, unobtrusive overhearing of ordinary conversation, Clampitt’s “I” engages with her fellow travelers from the beginning, and with the one of them in particular whose speech sounds already like poetry. It occurs to me, then, that if for Bishop the mystery is how ordinary experience can become a poem, for Clampitt the mystery is more like how an ordinary woman can join, midstream, a torrent of poetic language that is, to her, foreign.

The fact that the train is heading from France to Italy, and that the fellow traveler recites Petrarch and then Sappho suggests that Clampitt understood her vocation (and yes, to anyone else hearing it, odd that two episodes in a row, this and the Allen Grossman, might be described as poems about poetic vocation that take place on trains) as one that called her into a specifically European lyric tradition, one in which women have a particular and fraught role (see also the previous episodes on Andrew Marvell and Liz Howard).

Clampitt, it seems to me, is trying to “wedge” herself into that set of fellow travelers, and (here’s part of what makes the poem so distinctive) she’s doing so with a mixture of pleasure and confusion, which turns out to be, as it were, just the ticket. As Willard puts it so well, “She’s expressing a sense of exhilaration that has a concomitant sense of exhaustion with it.” What exhilaration and exhaustion jointly produce is an experience in which the noises of the train sound like language and language sounds like the noises of a train.

There’s a kind of delicious serendipity and romance to an experience like this. Willard compares the intimacy of the encounter in the poem to lines that he quotes from Charles Tomlinson’s poem “The Chances of Rhyme”: “The chances of rhyme are like the chances of meeting— / In the finding fortuitous, but once found, binding.” A sudden intimacy with a stranger on a train can feel both arbitrary and like destiny, as can (in a fortuitous note we sound at episode’s end) the intimacy between poet and reader.

Willard Spiegelman is the author of Nothing Stays Put: The Life and Poetry of Amy Clampitt (Knopf, 2023). He was for many years the Hughes Professor of English at Southern Methodist University and the editor of the Southwest Review. He is the author of eight books of literary criticism and writes regularly about art and literature for The Wall Street Journal.

Once again, you can find the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. As ever, please make sure you’re following the podcast and leave a rating or review if you like what you hear. Share an episode with a friend—or, for that matter, with a stranger on a train.

More soon!