Virginia Jackson on Phillis Wheatley ("To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth")

Close Readings: Episode 18

Who is the “I” in a poem? How do poems imagine the relation between the person (is that even the right word?) whom that pronoun names and the person who wrote the poem? (Have all of our poems had an “I”? Most of them have; perhaps others have implied one.)

That question is an urgent one at the heart of this episode’s poem, Phillis Wheatley’s “To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth,” and it’s also a fundamental question about the kind of poetry we have come to call “lyric.” So it was a real privilege to get to talk about it with Virginia Jackson, a scholar who has been thinking long and hard about how the genre of lyric has been made historically (in fact she is, among many other things, the author of the entry on “lyric” in The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics).

You can find our conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts.

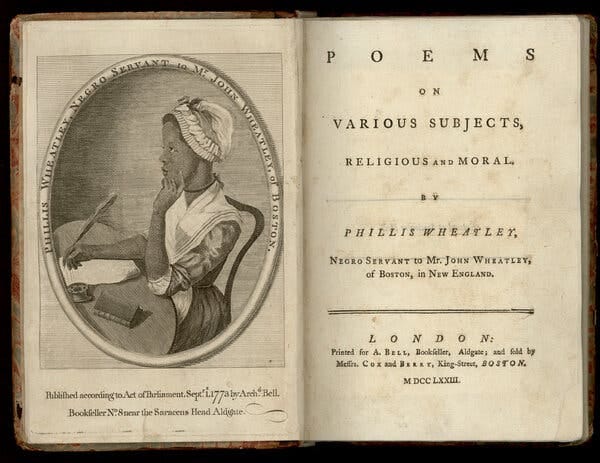

Phillis Wheatley was kidnapped from West Africa when she was a young girl, around seven years old, enslaved, and brought to Boston on board a ship called the Phillis, where she was sold to the Wheatley family in 1761. Her real name, in other words, was taken from her and forgotten, and in its place we have the name of the ship that carried her and the family that enslaved her. In this episode, Jennie Jackson tells the story of how this young girl very quickly demonstrated a talent for language and literature, began to write poems, and soon after became famous on both side of the Atlantic, in the years just before the American Revolution, as a published poet.

Much of our conversation is about how Wheatley managed in her poems to address the various occasions of her writing. As Jennie explains it, in a quite literal way in this poem—but perhaps more broadly throughout her oeuvre—that occasion was a trial of her identity, and indeed of her personhood and claims to freedom.

The more proximate occasion of this poem was the appointment of a new British Secretary of State for North America, William Legge, the Earl of Dartmouth. Wheatley’s poem celebrates his appointment, briefly narrates her own life story, and seems, for a careful reader, to set in place a kind of undeniable emancipatory logic:

I asked Jennie to talk about what was happening in the poem when, in its penultimate stanza, an “I” emerges and tells something like a life story. Here is some of what she had to say:

When the “I” comes in, the question you’re posing, which is really for me the question of the poem, is this person, this misnamed person “Phillis Wheatley,” talking about her experience before the Middle Passage, or her history—that is she’s “snatch’d from Afric’s…happy seat”—or is that line, “Such, such my case,” the important line in this argument? That is, she’s using her case as one case among millions, by this point, as a case in the revocation of freedom.

Was the “I,” in other words, a simple autobiographical pronoun whose referent was the young girl kidnapped and enslaved in 1761, or was Wheatley telling a generic story whose contours would have been familiar and of which she was merely an example? Both things at once, Jennie says, which is the power of the poem:

What she’s doing is collapsing them on each other. That doesn’t mean that it’s not personal. It means that the personal is the generic. As Glissant would say, “consent not to be a single being.”

There’s so much in this conversation that I’ve kept thinking about since we talked. Listen also for the discussion of rhyme—Wheatley tended to write in rhyming couplets of iambic pentameter, not unlike Alexander Pope, say—where Jennie brilliantly suggests how the technology of rhyme allowed Wheatley to open up a space in the middle of sets of binary constraints.

Some links to work on Wheatley (and other things) that come up in the conversation:

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, The Age of Phillis.

The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley. This is edition published as part of The Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers, in collaboration with Oxford UP, for which Henry Louis Gates is the general editor (the volume’s editor is John C. Shields). Gates is also the author of The Trials of Phillis Wheatley.

You can read more about the Somerset case here.

When we talk about Wheatley’s couplets, Jennie cites the work of James Ford III, and his book-in-progress, Phillis, the Black Swan: Disheveling the Origins of African American Letters. His faculty profile is here. Jennie also refers to the work of the scholar J. Paul Hunter on the couplets of Alexander Pope, which you can find an example of here.

David Waldstreicher has just published a new biography, The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley.

Rinaldo Walcott, The Long Emancipation.

Édouard Glissant uses the phrase “[consent] not to be a single being” in this interview.

Jennie also refers to the work-in-progress on Wheatley by the scholar Dana Murphy, whose faculty profile is here, and who talks about Wheatley in this interview.

Virginia Jackson is the UCI Endowed Chair in Rhetoric at University of California, Irvine. She is the author of two monographs, Before Modernism: Inventing American Lyric (Princeton UP, 2023) and Dickinson’s Misery: A Theory of Lyric Reading (Princeton UP, 2005), and the co-editor, with Yopie Prins, of The Lyric Theory Reader (Johns Hopkins UP, 2014). Her articles have appeared in such journals as Critical Inquiry, MLQ, New Literary History, Studies in Romanticism, and PMLA.

Once again, you can find our conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. If you like what you hear, leave a rating and review, and make sure you’re following the podcast. Share an episode with a friend! And subscribe to this Substack, where you’ll get a newsletter to go with each episode.