I had the great pleasure of talking with Stephen Guy-Bray about one of the most perfect poems I know, George Herbert’s “Prayer (I)”. You can find the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. (And maybe elsewhere? I really am still learning how this all works!)

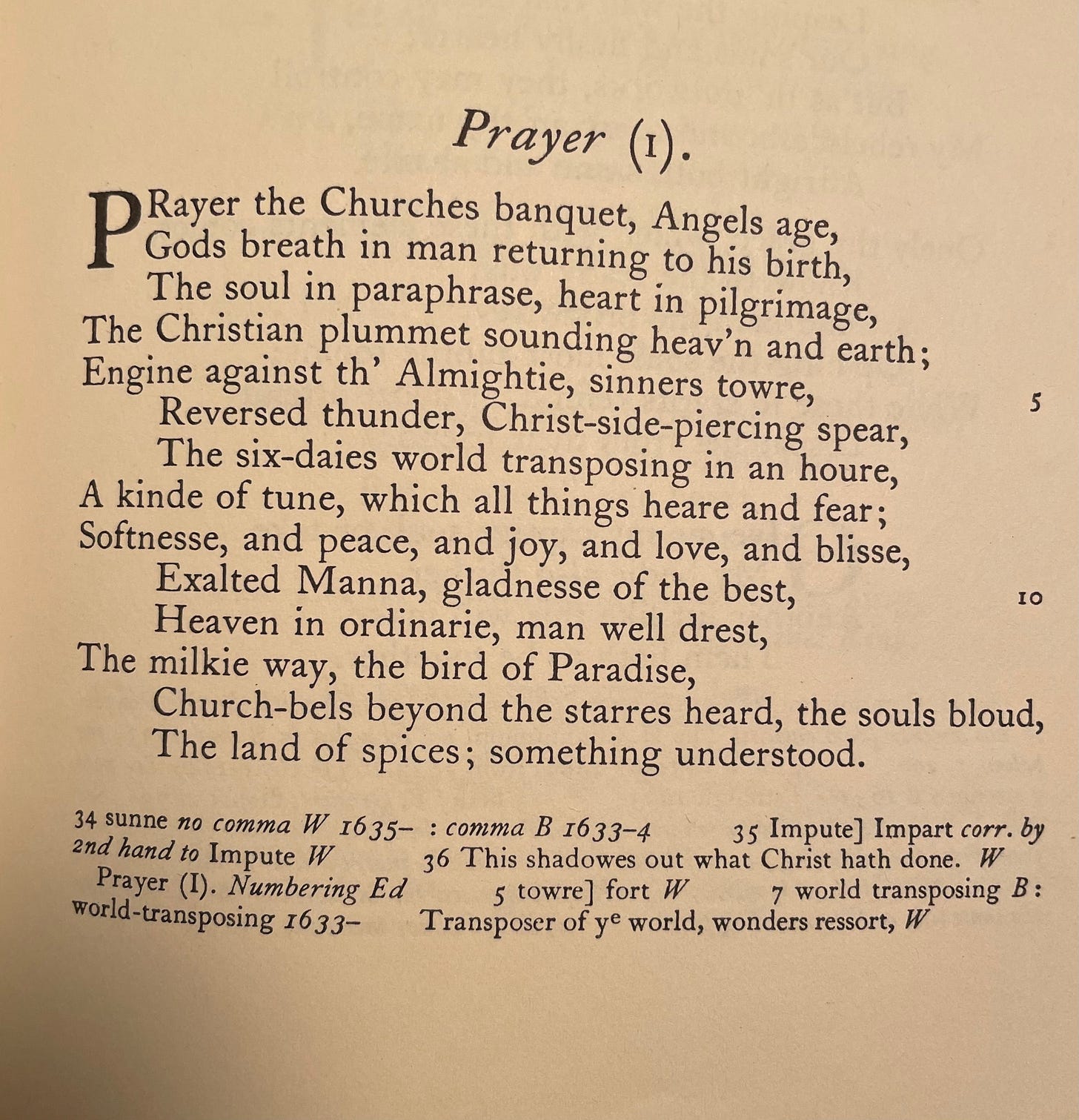

This is, so far, the shortest poem that we’ve had on the podcast—it’s a sonnet, so just 14 lines—which means that we really were able to proceed almost line by line, phrase by phrase, in our discussion. For me, there’s a particular kind of pleasure that comes from that sort of work, and I hope for you, too. I linked to the text of the poem above, but, for people who just want to see it, here it is in my Oxford UP edition of The Works of George Herbert.

One of the things Stephen and I talk about in the episode is the kind of speech act that prayer is, and how that might be like what happens when you read a poem out loud. As Stephen says, “This is not so much a poem that has a beginning, and a middle, and an end. It’s a poem in which all parts exist at the same time, even though when reading it, of course, you read it in a certain order.”

I think there’s a beautiful kind of tension—and you’ll hear it in the episode—between, on the one hand, that desire for a kind of poetry that could be understood completely and all at once, and, on the other, the method Herbert employs here, which is after all a sequential list of beautiful (and often beautifully vague) appositive phrases. If prayer is “a kind of tune,” then so too is poetry: an improvisation on or an ad hoc approximation of a structure we have in our heads. How did that tune get there? Well from church-going, if we’re talking about prayer, or from reading other poems, if we’re talking about poetry, or perhaps just from living, in either case.

One of my favorite moments in the conversation comes near the end, where we spend some time thinking about what it means that this poem ends with the phrase “something understood.” “Perhaps it’s the best ending of any poem ever,” Stephen says. Then goes on to say this:

Central to Christianity and I think to most religions is that the core of the religion is something that our puny human minds can’t understand, because it’s so much bigger than humanity. So “something” is as close as you’re going to get. Something’s understood, but he can’t tell us what it is, and perhaps when he prays he still doesn’t know what it is. But he knows that something’s been understood. And I would say “understood” goes both ways: it’s something understood by God, to whom he prays, but it’s something Herbert understands about himself and about God through the act of praying.

You’ll get the sense, I think, that something like this happens for Stephen when he reads a poem he loves.

Stephen Guy-Bray is a professor at the University of British Columbia and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. He is the author of five monographs: Line Endings in Renaissance Poetry (Anthem, 2022), Shakespeare and Queer Representation (Routledge, 2020), Against Reproduction: Where Renaissance Texts Come From (Toronto, 2009), Loving in Verse: Poetic Influence as Erotic (Toronto, 2006), and Homoerotic Space: The Poetics of Loss in Renaissance Literature (Toronto, 2002). In the episode we also refer in passing to a recent academic article of his called "Notes on the Couplet in the Sonnet" and to a recent talk he gave on "Aboutness in Shakespeare's Poetry." Follow Stephen on Twitter here.

Once again, you can find our conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. Please do leave a rating or review, and tell a friend about the podcast. More episodes coming soon!

Yet another really interesting episode. As a birder and "naturalist" I have to say that birds of paradise were misunderstood in Herbert's time as birds that flew continually their whole lives, living on "sky dew and sun rays," not coming down to earth until they died. The naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace wrote that spice traders who reached the Moluccas were presented with these birds, which the local's referred to as God's birds. See https://fashioningfeathers.info/birds-of-paradise/ So, for Herbert's contemporaries at least there may be some kind of connection between the line about the land of spices and the bird of paradise. And of course Galileo gave people a new idea about the milky way when he turned his telescope to it and saw the whiteness was actually "innumerable stars," which might relate to "something understood"--but I don't know when this poem was written.

This discussion was very interesting as I had read the poem several times before listening to the podcast and had a much simpler understanding of it. To me the sonnet was the full story of Christianity as I learned in the Catholic Church when I was still a child. God created man, man created Christ and the well-dressed wisemen came from the spice worlds to view the humbly dressed Virgin Mary and Joseph and the baby Christ at the manger!! You and professor Guy-Bray saw much more into it. He pointed out the difference between prayer in Protestantism, which is spoken in an individual free-form sort of way, and prayer in Catholicism, and other religions, which is spoken in a set form in unison or individually. I had not thought of that before. The last words “something understood” is what believers feel. It is a mystery. As a practitioner of Catholicism for a few years, I became an agnostic in later years. Today I am a non-believer. I think “something understood” applies to those who believe in the stories. My understanding of the sonnet is not academic but I wanted to share it anyway.