What is it like to live with the knowledge of the lives you didn’t live? I talked with the great Stephanie Burt about a poem that dramatizes this question, Randall Jarrell’s heart-stopping “The Player Piano.” You can find our conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts.

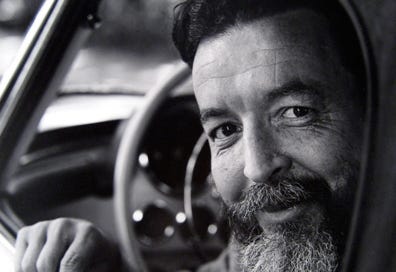

Here is an image of “The Player Piano,” taken from Jarrell’s Complete Poems.

This was a fascinating, poignant conversation for me. Partly of course because of the power and depth of feeling in this poem, which I hadn’t really known well before Steph told me it was what she’d wanted to talk about. It’s a poem that Jarrell wrote near the end of his life, and it’s one whose speaker is a woman a little bit older than the poet. In our conversation, Steph notes (with I think some combination of amusement, wonder, and sympathy) that this was a common move for this poet: “Jarrell made sounding like a disappointed, white, middle-aged adult woman one of his central aesthetic goals. He did it over and over.”

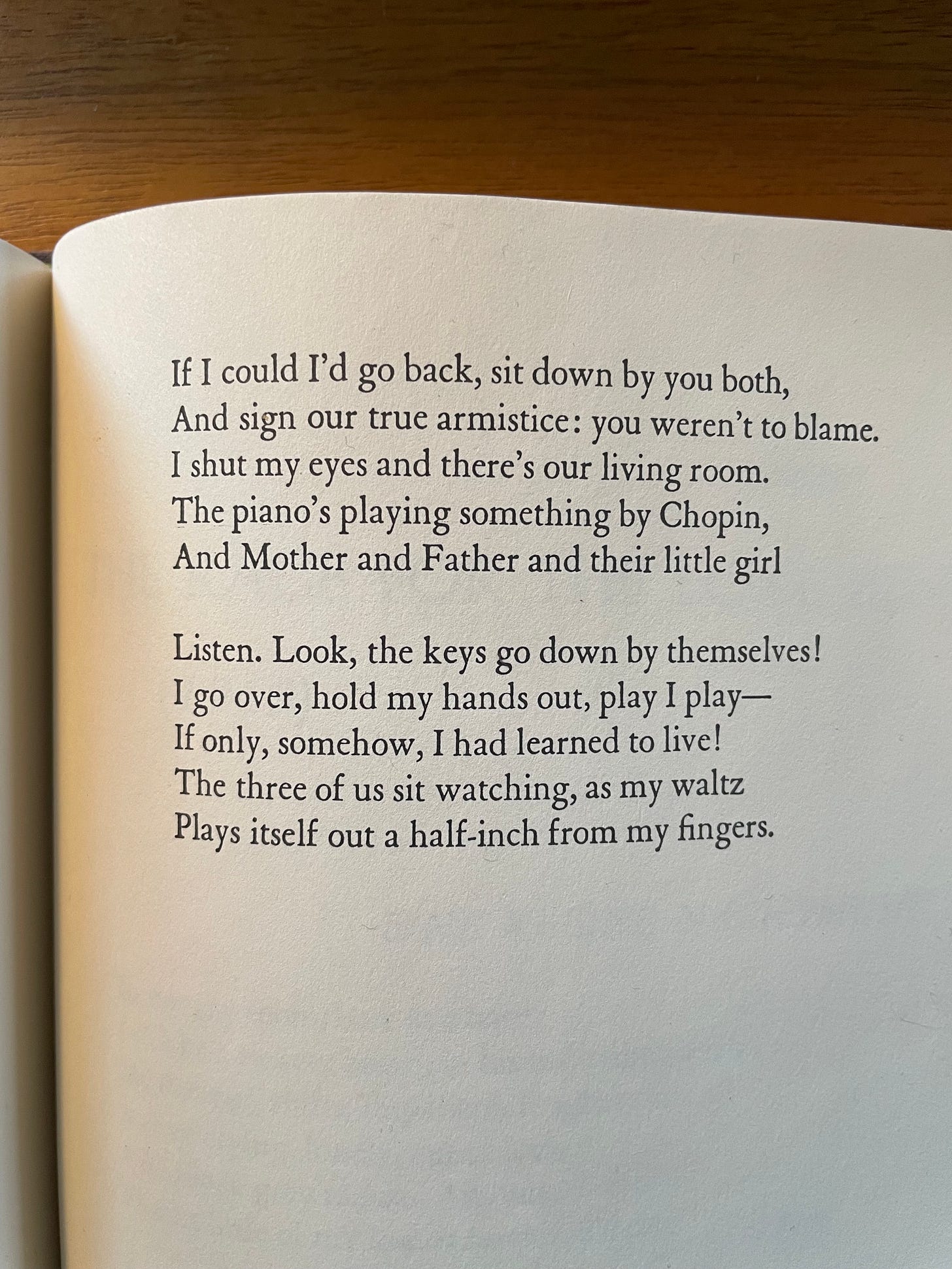

Here is the man who wrote the poem.

The particular version of this Jarrellian aesthetic effect that we get in this poem is intensely moving. Here’s some more of what Steph had to say about the woman who speaks the poem:

She’s looking back on the girl that she was and thinking, what did I do with that, who did she become, what happened to me? And the answer is nothing, it feels like nothing. Whatever it was I was supposed to do with my life, I missed it.

Incidentally, I found myself thinking, in this part of the conversation, about two other books: Adam Phillips’s Missing Out, and Andrew H. Miller’s On Not Being Someone Else.

As Steph notes, there is both something universal about the feeling that we have failed to live out some part of the potential we had as children, but there’s also a very specific version of that experience that we find in this poem, one that applies to this woman alone and to the particular course of her life:

The involuntarity of life moving on and aging just opens up like a river coming to a place where there’s a waterfall in those last eight [lines] where she shuts her eyes and we’re completely in her imagination: “I shut my eyes and there’s our living room.” She shuts her eyes and she listens and she knows that she’s not making that music. She is not in charge, she’s never been in charge of how her life turned out. She didn’t even learn to play properly. And the poem almost feints for me at the idea that it wants to be universalized, that we’ve all experienced this sense of what happened, I grew old, life went on without me, and then it zeroes in at this child doing something that not every child does, which is pretend to play the piano instead of playing it. And her unlived life and her body that didn’t belong to her then, that she didn’t take action with then, that she’s not taking action with now—she’s just standing in front of her mirror maybe with her eyes closed at the end of the day—the sense of helplessness there belongs to this character and just opens up the heart of this character. And I’m, at least, blown away.

So, as I say, part of what so moved me about this conversation had to do with the poem at its heart.

But then another dimension opens up, maybe about halfway through the episode and continuing on through its conclusion. Life intrudes, and in more way than one. For one thing, one of Steph’s children pops in with a brief interruption, and we hear the life of the family overlap for a moment with the poem at hand. Nothing, as we noted, could have been more in the spirit of the poem.

And things deepen from there. As Steph notes, when she wrote her (fabulous) book about Jarrell twenty years ago, “I didn’t know I was a girl.” Of course there’s a version of the idea of the unlived life that might apply to queer lives, to trans lives in particular. Steph tells me that she’s often asked to comment, given the course of her own life, on whether Jarrell might have been trans. She wisely insists that we grant the dead the pronouns they took in life, but also notes that there’s a lot of trans-ness at work in Jarrell’s poems, which so often inhabit, as it were, the subject position of women whose lives have been disappointments. I won’t say more about this part of the conversation here—but just enjoin you instead to listen to what Steph has to say on the topic.

Finally, though, we talk also about how Jarrell might have been a source of identification for Steph in one other way, having nothing necessarily to do with being trans. What is it like, I ask her, to have forged as a career as a critic who has never stopped writing poems? When she sits down to write, is the experience anything like sitting at a player piano, seeing the keys move without her touch?

Steph is Professor of English at Harvard University, where she works on poetry (particularly of the 20th and 21st centuries), science fiction, literature and geography, contemporary writing, comics and graphic novels, and literature alongside other arts. She is also a poet—her books of poetry include We Are Mermaids, After Callimachus, Advice from the Lights, Belmont, and Parallel Play. Her critical books include Don't Read Poetry, The Poem Is You, Close Calls with Nonsense, and Randall Jarrell and His Age. Steph regularly reviews new books of poetry and publishes essays in places like The New York Times Book Review, The New Yorker, The London Review of Books, and The Yale Review. She is also a cohost of Team-Up Moves, a podcast about superhero role-player games. You can follow Steph on Twitter.

Once again, you can find the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. If you like what you hear, make sure you’re following the show, and leave a rating or review, share it with a friend, etc. New episode coming in one week!

Loved this episode!

This was a fascinating and moving close reading of the poem. Thank you for another great podcast!