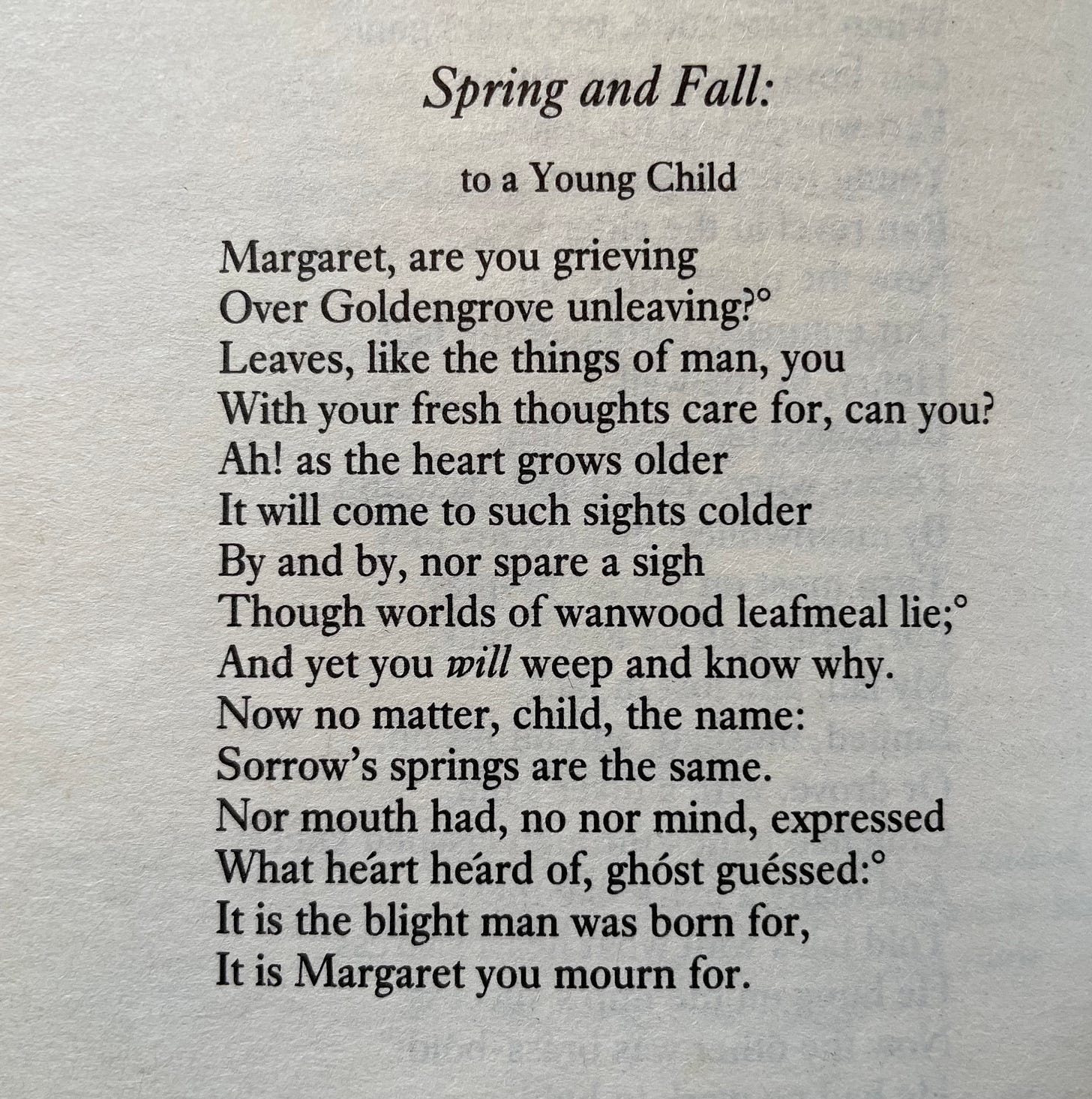

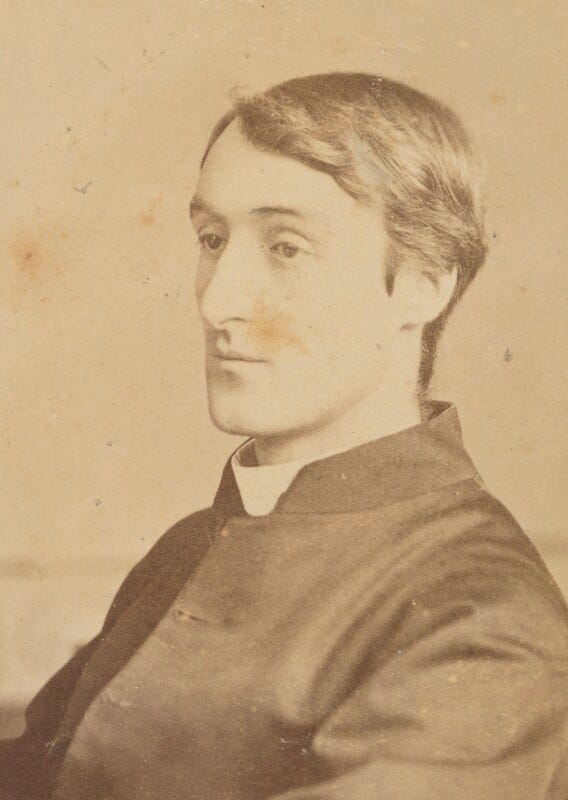

Certain poems feel perfect. What I mean is not necessarily that they are beautiful (though they might be), but rather that they feel inevitable, that when you read them you come to feel as though they couldn’t possibly have been any other way, that the poet hasn’t composed so much as discovered them, uncovered them already in their final form. Often, for me, that feeling emerges—or is suddenly cinched—in a poem’s last lines. This episode’s poem, “Spring and Fall,” by Gerard Manley Hopkins, is like that.

I talked about it with Maya C. Popa. You can listen to our conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. Here it is in my Oxford UP critical edition of Hopkins.

The poem has at its heart two kinds of time, two scales of measuring time’s passage (in this respect I am reminded of the conversation I had with Lindsay Turner about Bishop’s poem “The Shampoo”): on the one hand, an annual turning of the seasons, recorded by the falling of leaves and so on, and, on the other, the passage of a human life, from childhood through aging to death. The poem begins in a place where those measurements of time seem out of synch: the girl is in her youth (her Spring) and yet the leaves are falling. (In this sense maybe the poem’s temporalities are unlike those in “The Shampoo,” which felt concentric, synched up, etc.) The falling leaves are, for the girl who grieves them, a first intimation of mortality.

As it turns out, of course, she is both wrong about the tree and yet righter than she can know about its lesson. Here’s how Maya explains that paradox, which is beautifully captured in Hopkins’s strange word “unleaving”—does that mean “losing its leaves,” or “not going anywhere”? Both, it seems:

In reality the tree is going nowhere, it’s still alive, it’s dormant, it’s a season, it’s not leaving. And on the other hand she’s the one who’s going to leave…That tree existed before her and that tree will exist when she’s gone. In some ways, these are the spiritual exercises of nature, they are continuous. And we have our “seasons,” too, but we feel in much more emotionally taxing ways about our seasons than nature seems to feel. Nature does not seem to worry about its ebbs and flows, and we are in a constant state of neurosis about death.

The poet knows something that Margaret doesn’t know, or rather the poet knows something that Margaret grieves without knowing why, knows the source of her grief whereas she knows only its expression, so that the charge of the poem is to teach Margaret the words for what, at some level, she gets but can’t properly say.

That knowledge—that mortality itself, her own first of all, is the true source of her grief—is something life would have taught her even if the poem hadn’t, so that the seeming inevitability of the poem’s articulation, what makes it seem “perfect” to me, is its alignment with the certain logic of death. “She will have internalized the source of her own grief,” Maya explains, “and it won’t be what she thought it was.”

But for me the real brilliance of the poem hides within one of its simplest choices: the use of the girl’s name, “Margaret,” in its final line: “It is Margaret you mourn for.” Hopkins might have written “It is yourself you mourn for,” but using her name there makes it feel as though there is some entity called “Margaret” that exists apart from the girl who is hearing the poet’s message: an instance of self-estrangement that works as a harrowing intimation of the way death makes people into objects.

The name is itself an interesting one. Etymologically, the name “Margaret” means “pearl.” When I told Maya about that in the episode, she offered the brilliant thought that Hopkins may have had in mind the Middle English “Pearl” poem, itself about the death of a young girl. (Victorianists out there: does this seem likely? Is it commonly observed?)

I have an even screwier theory, though, which is that “Margaret” shares (most of) its consonants with “Gerard Manley Hopkins.” So that, in other words, the didacticism of the poem is, at the end of the day, autodidacticism. Margaret thinks she grieving for a tree when really she’s grieving for herself. Hopkins thinks he’s teaching her a lesson about death when really the one who needs to learn that lesson is himself. Death, in this way of thinking, is the name for the pearl produced by the sands of life.

Maya C. Popa is a poet, critic, scholar, and teacher. She is the author of two full-length collections of poetry: American Faith (Sarabande, 2019) and Wound is the Origin of Wonder (Norton, 2022). She is the poetry reviews editor at Publishers Weekly and teaches creative writing at the Nightingale-Bamford School and NYU. Maya has a Ph.D. from Goldsmiths, University of London, on the role of wonder in poetry, a topic she writes about in her Substack. You can also follow Maya on Twitter.

I promised in the episode to link to some of Maya’s poems—here are three recent ones I’ve loved: “Dear Life,” “Reprise,” and the one I quoted in my intro, “The Present Speaks of Past Pain.”

Once again, you can listen to our conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. As ever, make sure to follow the podcast on whatever service you’ve found it, and leave a rating or review. Share an episode with a friend! And subscribe to this Substack, where you’ll get a newsletter to go with each episode. More episodes soon…

I.A.Richards includes the poem in his book Practical Criticism, drawing contrasting response from different readers. What I found illuminating here possibly in what one respondent said about the middle line is the idea that it refers to the child weeping now and wanting an answer. If so, this would make the rest of the poem an answer to the child's insistence. Secondly, it may be instructive from the point of view that Hopkins is personally involved in the grieving that colour is going out of Goldengrove. Spelt from Sybil's Leaves mourns the sense of Judgment reducing the whole world in all its variegated hues to black and white.

An interesting counterpoint to this poem is Byron's On The Death of a Young Lady (1802), in which the young lady is also named Margaret, and is also the dedicatee of the poem. Byron's poem opens in a grove at dusk. Margaret is dead, and the poet grieves while reminding himself of her eternal soul. "But wherefore weep? Her matchless spirit soars / Beyond where splendid shines the orb of day". In Hopkins's poem, which opens in "Goldengrove unleaving", the grieving has turned purely internal: the poet observes young Margaret mourning for her own ineluctable fate: a fascinating internalization and compression of time. Hopkins seems to deny his Margaret the redemption offered by Byron's Providence. He remains squarely with the sorrows of the living: "It is the blight man was born for."