I’m sitting here writing this on a dark, cold night in a mostly empty house, but I have my teacher’s voice in my ears, and I get to share it with you, and that does bring me joy. This episode felt like an indulgence to me, but ’tis the season, right? I hope it will feel to you like a gift. I talked with Langdon Hammer about James Merrill’s poem— almost the very last one Merrill wrote—“Christmas Tree.”

You can find the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts.

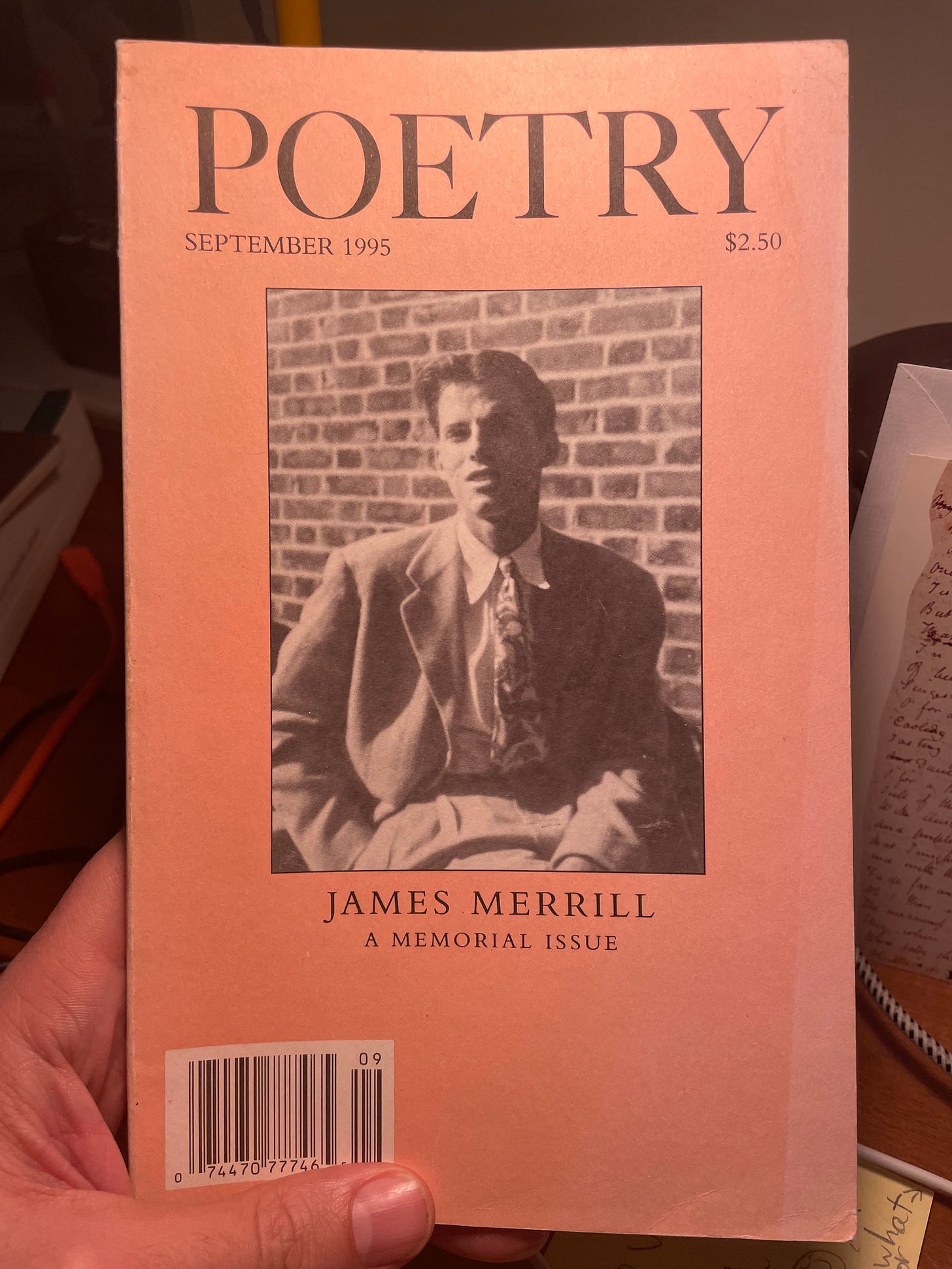

One of the first things Lanny and I talk about in the episode is the poem’s shape. Merrill, whose health was already in a steep decline, had begun to write it in New York City in December, 1994, and finished it in a hospital bed in Tucson, Arizona, shortly before his death on February 6, 1995. The poem was first published later that year, in this issue of Poetry.

In the magazine, Merrill’s “Christmas Tree” looked like this.

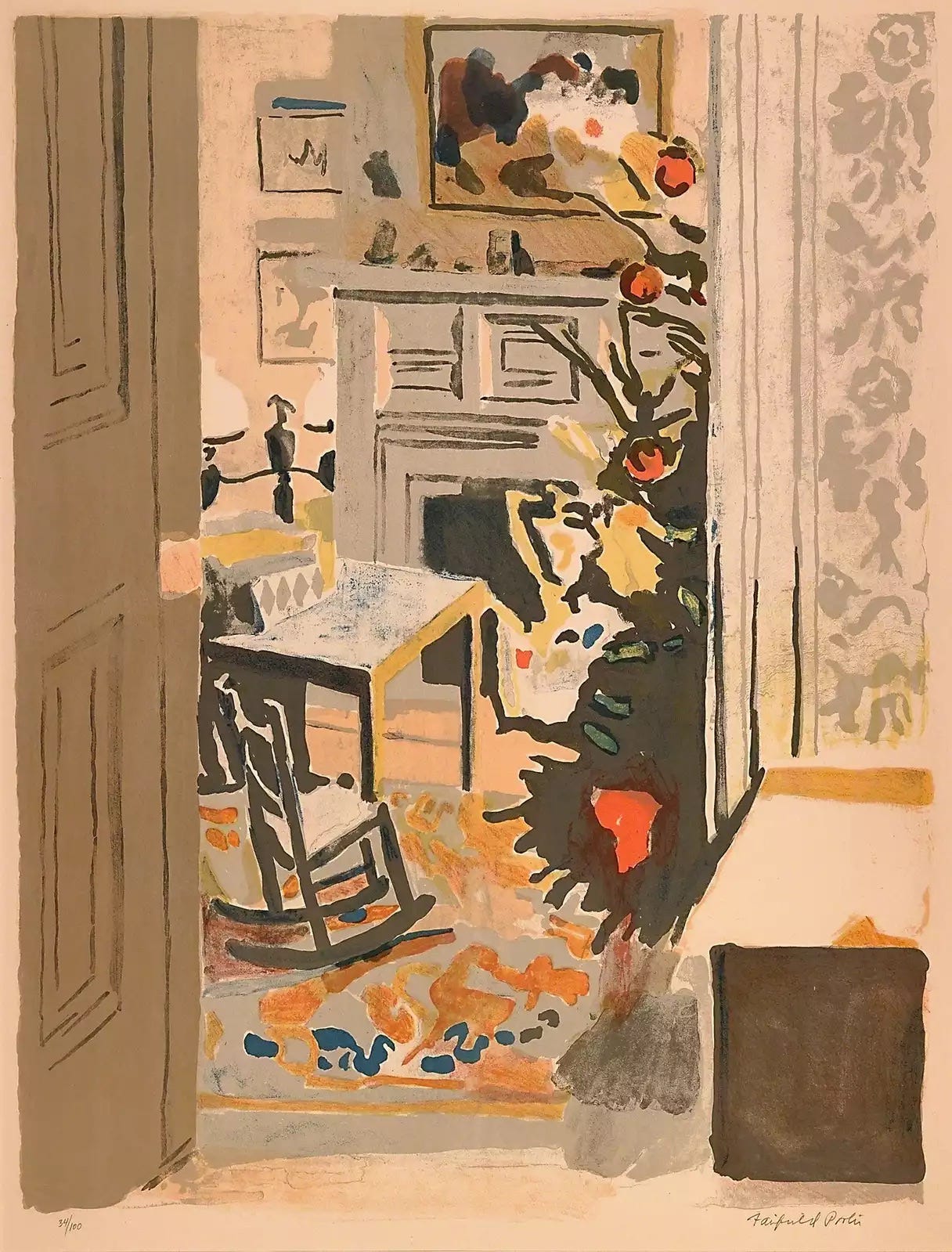

According to Lanny, though, Merrill had had a slightly different shape in mind. It seems he may have been inspired by his partial view, from bed, of the tree in the next room, the living room of his New York City apartment. And by remembered trees. And also by this Fairfield Porter print.

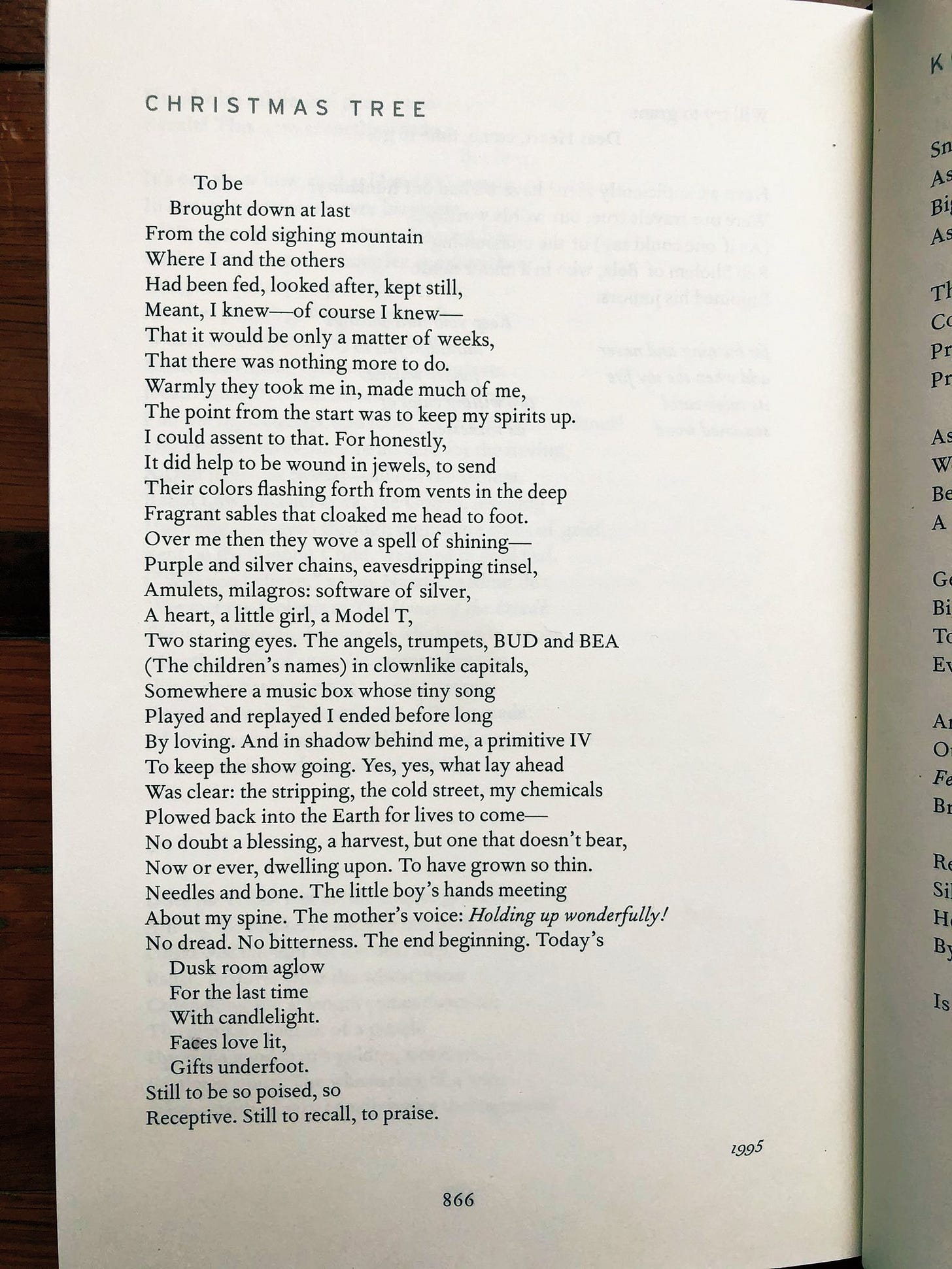

The Christmas tree as seen from another room, the viewer at some distance, some oblique angle, from the ritual it organizes. As Lanny explains in our conversation, if a Christmas tree is a symbol for a certain normative ideal of the nuclear family, then that is a scene from which the childless, queer Merrill might have felt at least partially alienated. If the tree is a sign of life, then how poignant that its green can only be glimpsed, by the sick and dying poet, from the next room. When J. D. McClatchy and Stephen Yenser published “Christmas Tree” in Merrill’s Collected Poems (Knopf, 2001), they restored its shape to Merrill’s vision.

Towards the end of our conversation, Lanny asks, “Why do we put up Christmas trees?” Here is how he answers his own question:

We put them up to celebrate the renewal of the world, in darkness. To bring living things into our home. To gather families—or, at any rate, loved ones—around that particular symbol. In that way, at the simplest level, a Christmas tree is life-affirming. And in that way we can understand it as a kind of praise.

To be poised, to be receptive, to recall, to praise. These, according to Lanny, constituted for Merrill a credo, in poetry as in life. And in death.

One thing I can say about this conversation, now that I’ve had it and listened to it again, is that it has made me more receptive to the gift of the poem. I hope it does the same for you.

Langdon Hammer is the Niel Gray, Jr. Professor of English at Yale University and the author of James Merrill: Life and Art (Knopf, 2015). With Stephen Yenser, he edited A Whole World: Letters from James Merrill (Knopf, 2021). He is also the author of Hart Crane and Allen Tate: Janus-Faced Modernism (Princeton, 1993) and the editor of Library of America editions of Crane and May Swenson. He is poetry editor at The American Scholar and a contributor to The New York Times Book Review, The New York Review of Books, The Yale Review, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. You can find a free, online version of "Modern Poetry," one of his Yale University undergraduate lecture courses, here.

Once again, you can listen to the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. Leave a rating and review? And happy holidays, friends. Here’s to more life in the new year.

Very enjoyable and illuminating!

Superb! Thank you!