“The poem must resist the intelligence / Almost successfully.” One of modern poetry’s great opening jokes (right up there with Marianne Moore’s “I too, dislike it”), a line and a half I have been carrying around in my head for years. I got to talk about the poem that it begins, Wallace Stevens’s “Man Carrying Thing,” with the great Kimberly Quiogue Andrews. You can listen to the conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts.

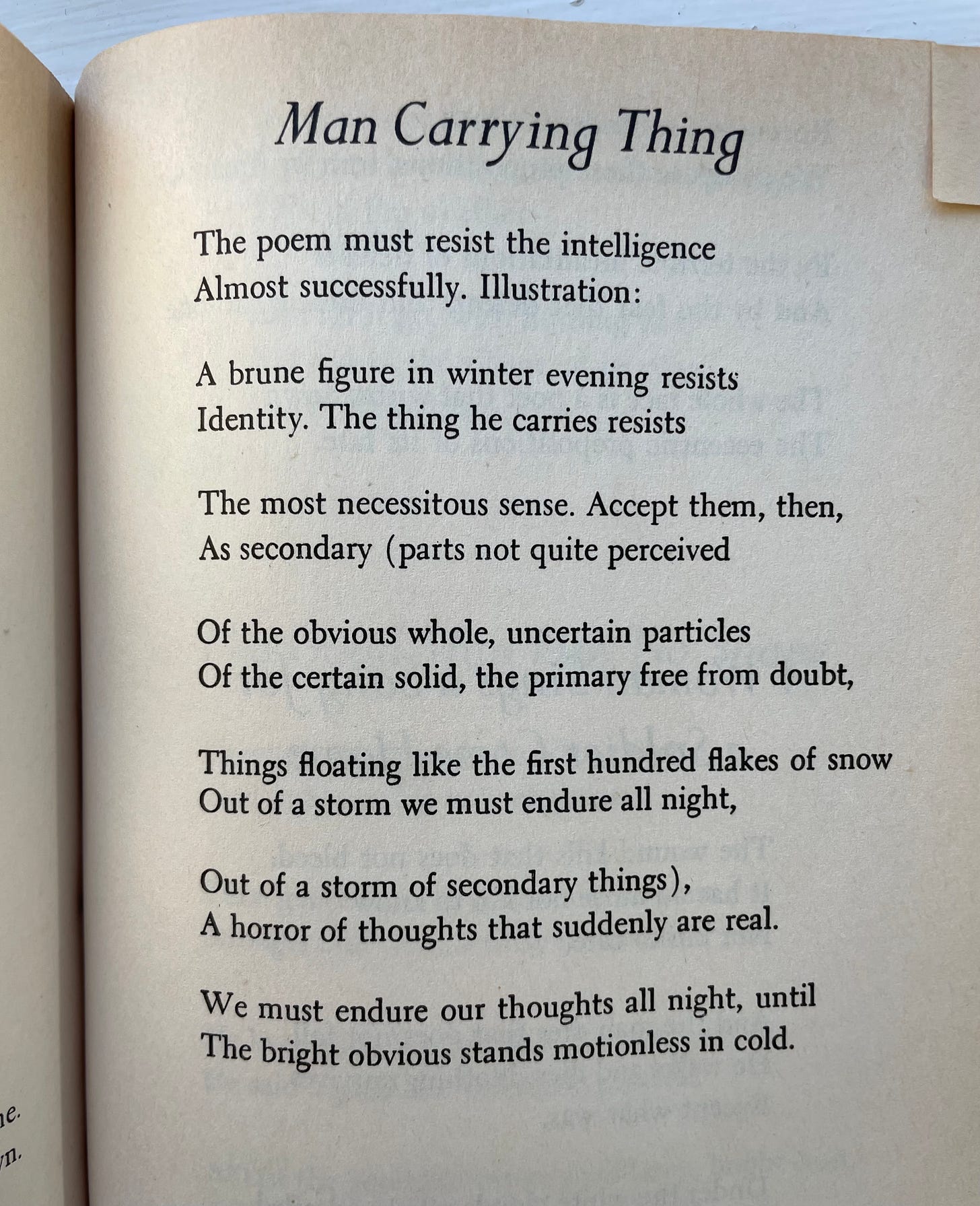

The poem was first published in book form in Stevens’s Transport to Summer (1947). For those who like an image, here it is in my edition of The Palm at the End of the Mind.

Kim is someone who approaches poetry from (at least) two angles, and who thinks carefully about the historical relation of those two approaches. She is, on the one hand, a poetry scholar like me (indeed our periods and interests overlap in many ways) and has just published an academic monograph and has published several articles in scholarly journals. But she’s also (unlike me!) a poet, the author of two collections, and a teacher of creative writing. The story of poetry in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, particularly in the United States, is one in which these two approaches—call them academic and creative—flow together into what increasingly looks like a single stream. These days it’s hard to find a practicing poet who doesn’t also have an academic position of some kind. As it happens, Kim’s research is about the implications of that historical development (which of course her own career is a prime example of).

This episode’s poem, “Man Carrying Thing,” sits at something like the beginning of that process, the absorption of poetry by the academy—and is deeply uneasy about it. That’s part of what motivates that opening joke: “The poem must resist the intelligence / Almost successfully.” Poetry wants to keep itself out of the glare of the kind of scrutiny scholars provide. But its resistance is always only almost successful: poetry must be resigned to putting up a good fight—and then losing.

What I’d never thought about before—before I talked to Kim that is—is that the “intelligence” that the poem “must resist” might just as easily be the intelligence of the poet writing it as it is the intelligence of the person reading it. I had always read it the latter way. For Kim, though, both meanings of the opening line are operative. Seeing how that might work, through her eyes, changed the poem for me.

To take Kim’s reading seriously, in which the poem must resist the intelligence of the poet (almost successfully), no longer is this primarily a poem that defends modernist difficulty, or anything like that, really. Instead, it’s a poem that expresses a desire to be inspired by something like a muse, so that what makes a poem possible is the poet keeping their “intelligence” out of the scene of writing, letting something else take over. But of course this attempt is only “almost” successful: picture Stevens trying to keep his own thoughts out of the poem, trying to be something like a Romantic poet (think back, for instance, to the conversation with Anahid Nersessian on Keats and “negative capability”), trying and then failing.

Stevens opens his eyes and sees that his thoughts fill the room, “like the first hundred flakes of snow” in a storm he “must endure all night.” There’s a great kind of pathos in seeing the poem this way—an attempt and a failure to be one kind of poet, and a making do with the storm one’s in, with the kind of poet one has to be.

Here’s how Kim begins to explain her brilliant reading:

One of the things that makes me partial to this reading of the first part of the poem is because you see this everywhere in Stevens: his old-school, Romantic desire towards a kind of expressive quality in poetry and what we wind up with, which is maybe some of the most obviously abstractly philosophical poetry of the twentieth century. He just can’t stop himself from thinking. He’s just constantly thinking.

Links to a few things that came up in the episode:

Stevens’s great poem (the one he said got at “the essential gaudiness of poetry”), “The Emperor of Ice-Cream”

Another early and great poem by Stevens, whose echo Kim hears at the end of “Man Carrying Thing,” “The Snow Man”

A series of blog entries by the poet Timothy Donnelly on this poem and related matters (Parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and a coda)

Kim’s article on this poem in Modernist Cultures

Kimberly Quiogue Andrews is an assistant professor of English at the University of Ottawa and the author of The Academic Avant-Garde: Poetry and the American University (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023). She's also a poet who has published two collections: A Brief History of Fruit (University of Akron Press, 2020) and BETWEEN (Finishing Line Press, 2018). She's the winner of the Akron Prize for Poetry, the New Women's Voices Award, the Ralph Cohen Prize for Criticism, and a development grant from the American Council of Learned Societies. Her essays and scholarship have appeared in such publications as The Los Angeles Review of Books, Contemporaries at Post45, Modernist Cultures, and New Literary History. Her creative work has appeared in The Florida Review, The Asian American Literary Review, Poetry Northwest, and Crab Orchard Review. Follow Kim on Twitter.

Once again, you can listen to our conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. Leave a rating or review if you like what you hear, and share the episode with a friend. Finally, follow me here to get a newsletter in your inbox with each episode. More soon!

Re: your discussion about Stevens and winter: Being French, the last couplet of this poem rings very Mallarméan to me. I’m thinking in particular of « le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd’hui », a sonnet that Edmund Wilson quoted in full in Axel’s Castle, his highly influential history of modernism (which Stevens might have read, though he might easily have come across Mallarmé’s poem elsewhere). Mallarmé’s poem depicts a frozen and motionless landscape—in which an exiled “swan of yesteryear” is condemned to the impossibility of flight—as the Ur-landscape of modern poetry: a space in which former Romantic symbols become frozen in splendid isolation and mutism. There is likewise a movement towards definition in “Man Carrying Thing”, a slow crystallization (despite resistance) through the night until we get to the bright obvious: the day, the frozen swan, the completed poem? The phrase “the bright obvious” with its nominalized adjective, also seems like a gallicism and sounds quite similar to “le bel aujourd’hui”.

(Note too that “la brune” is a word Mallarme uses several times (afternoon of a faun and other poems). Anthony