I am, as they say, “comically behind” on putting out these newsletters to accompany the podcast episodes, so by now I expect that most of you will already have listened to my conversation with Harris Feinsod about William Carlos Williams, Spring and All, and the poem from that book that would eventually come to be known as “To Elsie.”

So consider this a hasty reminder from the near past and a brief assemblage of texts and images and links that might supplement that conversation. You can find the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts.

One occasion for our conversation is that this year marks the centennial of Spring and All, though, as we note in the episode intro, Harris is interestingly and persuasively on the record as “against centennials.” As you’ll see if you look at that essay, much of Harris’s feeling of dread about such commemorations came in the run up to the centennial of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922), a poem to which, a year later, Williams was quite directly responding in Spring and All (1923).

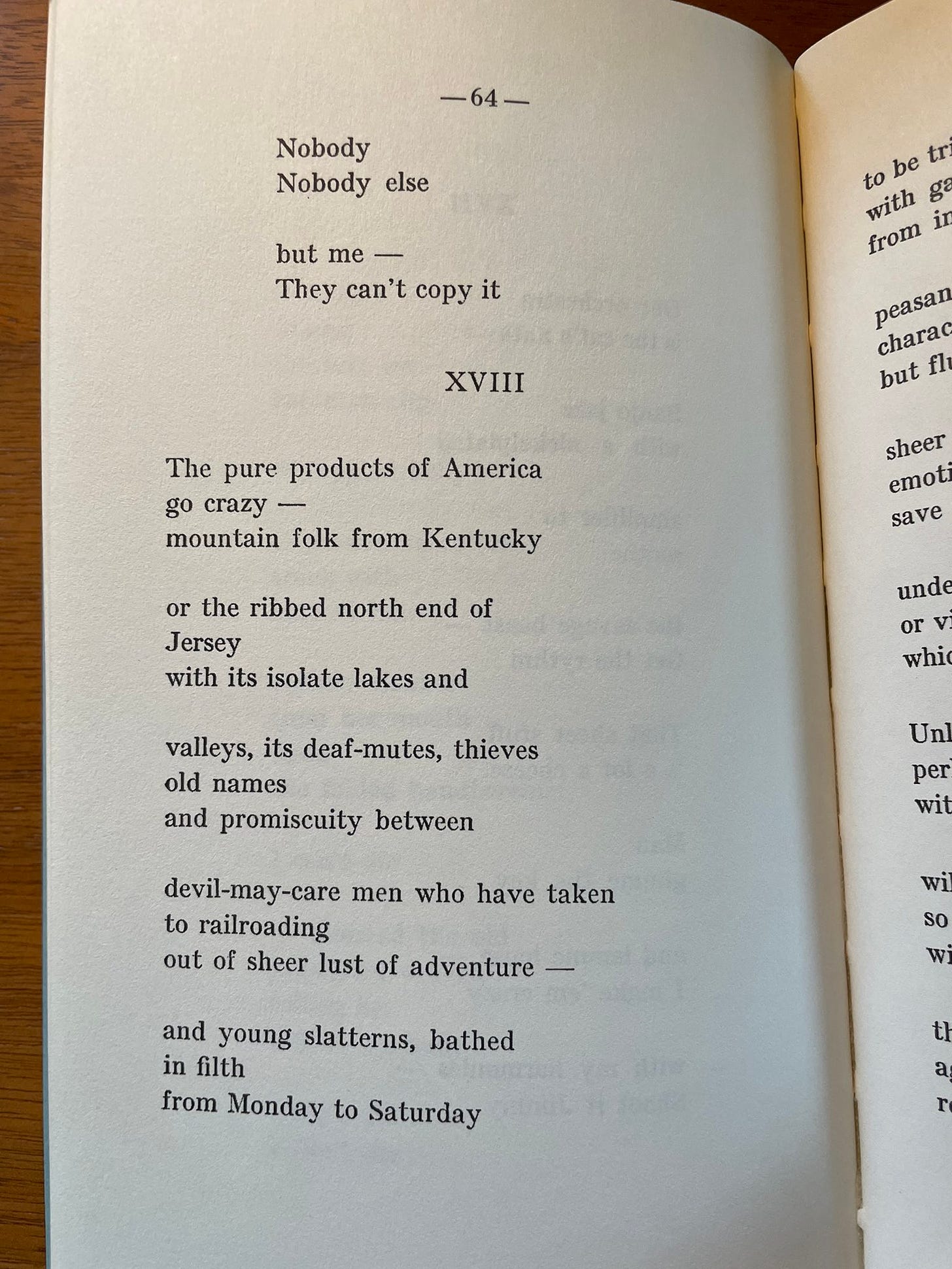

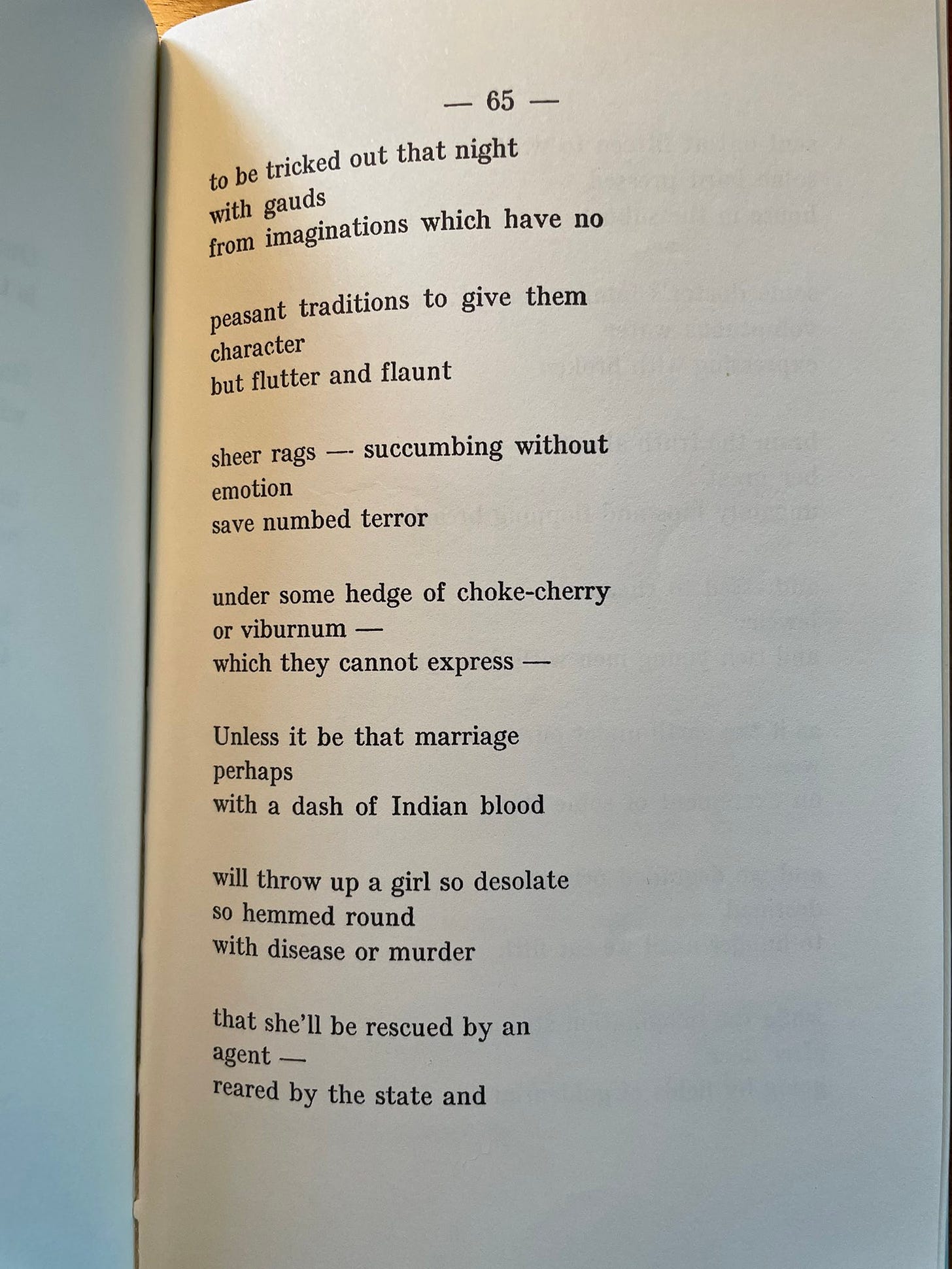

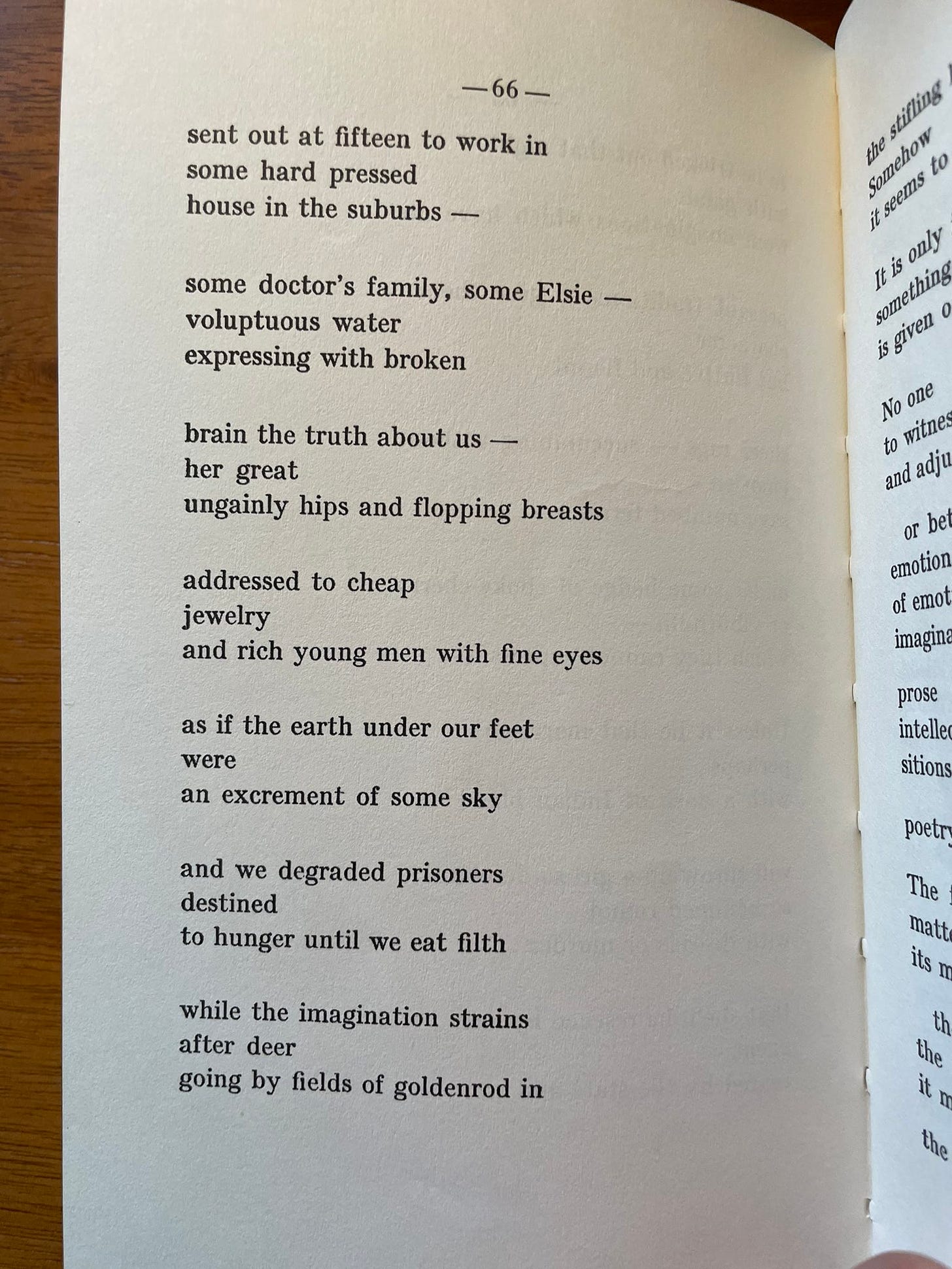

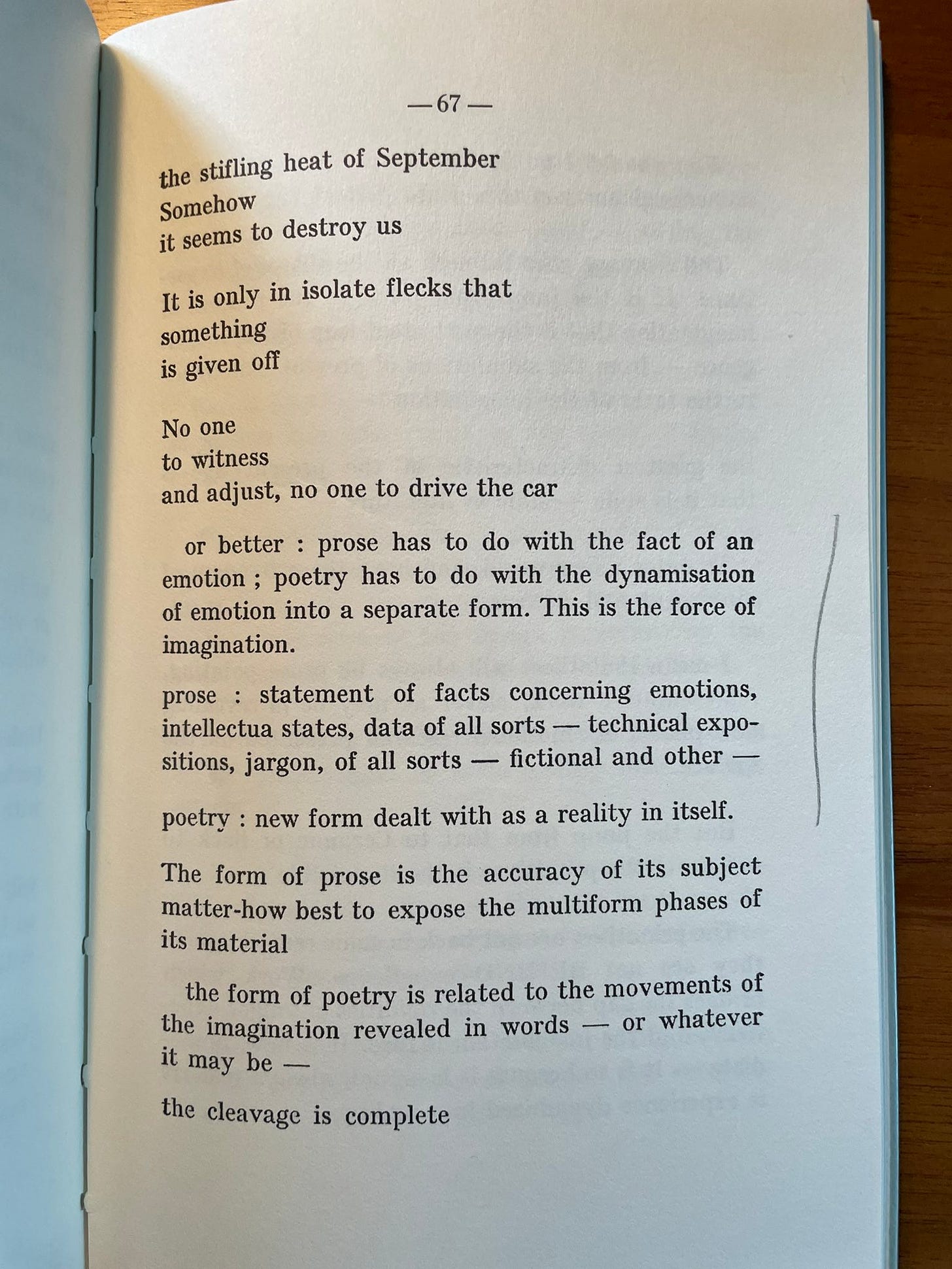

Here’s how the poem looks in my facsimile edition of that book (which is, as Harris points out, a book that is both experimental or avant-garde in its approach to form and in the long tradition of “prosimetrum,” a book that mixes verse and prose):

Harris refers near the beginning of our conversation to the anthropologist James Clifford, who uses this poem as a way into talking about “what the ethnographic project had been,” in his book The Predicament of Culture (Harvard UP, 1988). Harris wants to read this poem as an instance of Williams responding to a related “predicament” being faced by poets, writers, and artists across the Americas: what, in the modernist period, constituted “purity” in multiracial, multiethnic, settler societies?

Two things emerge in response to this question during our conversation: for one, Williams is taking on a question not entirely unrelated to the cosmopolitan, multilingual ambition of Eliotic modernism, though Williams seems much more determined than Eliot to remain rooted in American soil as he pursues these lines of inquiry. For another, Harris talks about the question of Williams’s own multiethnic background and surveys some recent scholarship that asks whether we ought to consider Williams a poet in the Latin/x tradition.

That’s not a question we try to resolve (and how could we?) here, but as metonym for some directions in which it might lead, Harris notes that while Williams himself was perhaps more inclined to identify as anglo, and while he writes from within the structures of whiteness, he was at the time seen by his peers, and in particular by his friend and fellow modernist Ezra Pound, as an outsider. Pound responds to Williams’s early work by asking him, in a 1917 letter, “And America! What the hell do you a bloomin’ foreigner know about the place?” Harris wants us to see the paradox in the fact that Williams, the American modernist who stayed in the United States, was nevertheless apprehended as a foreigner. And to see how that paradox must in some sense have underwritten Williams’s own ethnographic gaze, his own poetic investigation of “the pure products of America.”

Harris Feinsod is an associate professor of English and Comparative Literary Studies at Northwestern University. He is the author of The Poetry of the Americas: From Good Neighbors to Countercultures (Oxford UP, 2017) and the co-translator (with Rachel Galvin) of Oliverio Girondo’s Decals: Complete Early Poems (Open Letter, 2018). Harris's articles and essays have appeared in such publications as Comparative Literature, American Literary History, English Language Notes, Modernism/modernity, The Baffler, In These Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, n+1, and Post45. You can follow Harris on Twitter.

Once again, you can find the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. As ever, if you enjoy the podcast, please leave a rating and review and share an episode with a friend. And subscribe here, where I’ll have more for you soon!