“It’s a day like any other.” That’s the final line of James Schuyler’s “February,” a poem that I had the great pleasure of discussing with my old friend, the scholar Eric Lindstrom, for an episode that I want to share with you today, “at five p.m. on the day before March first.”

You can listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts.

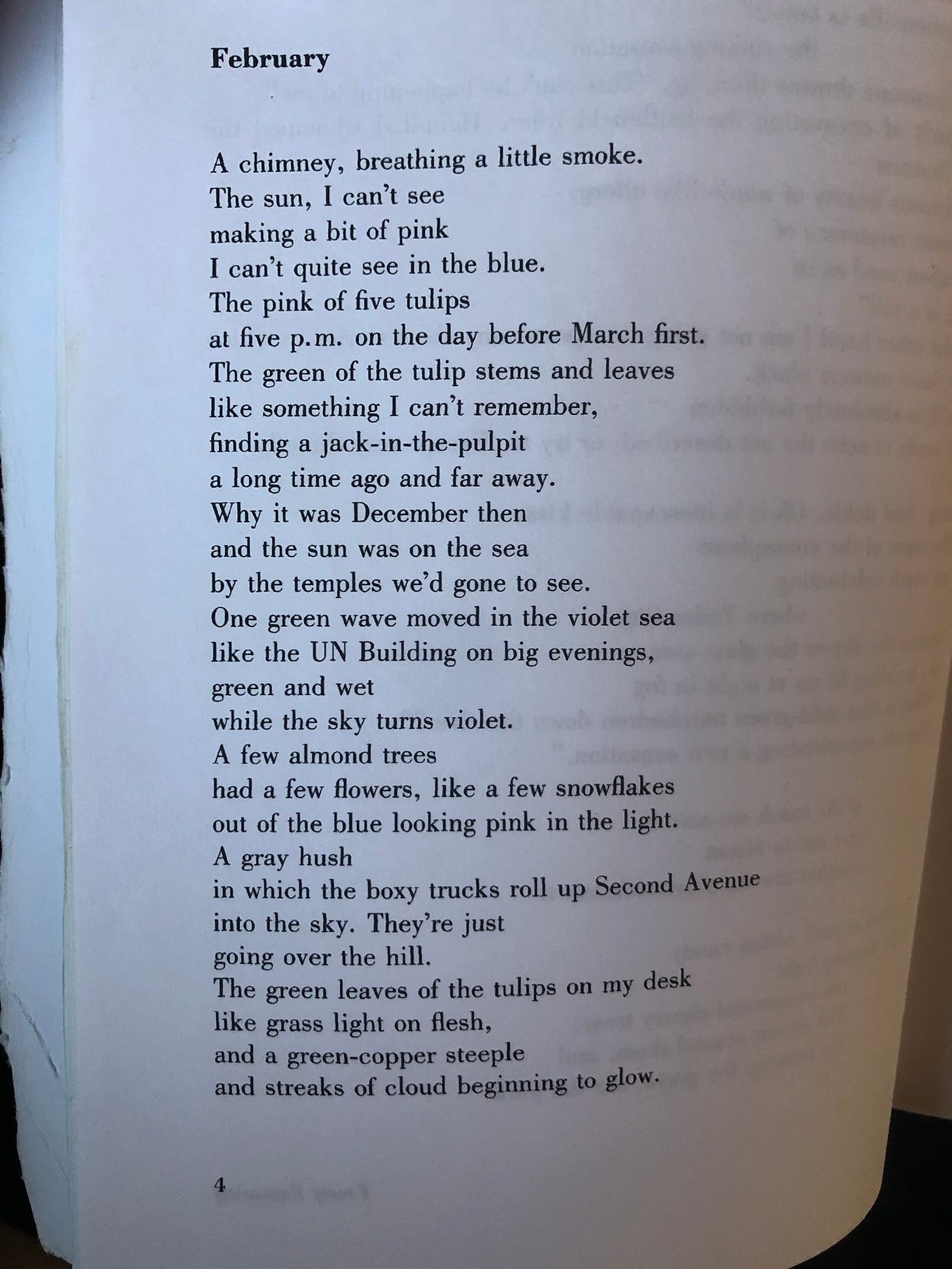

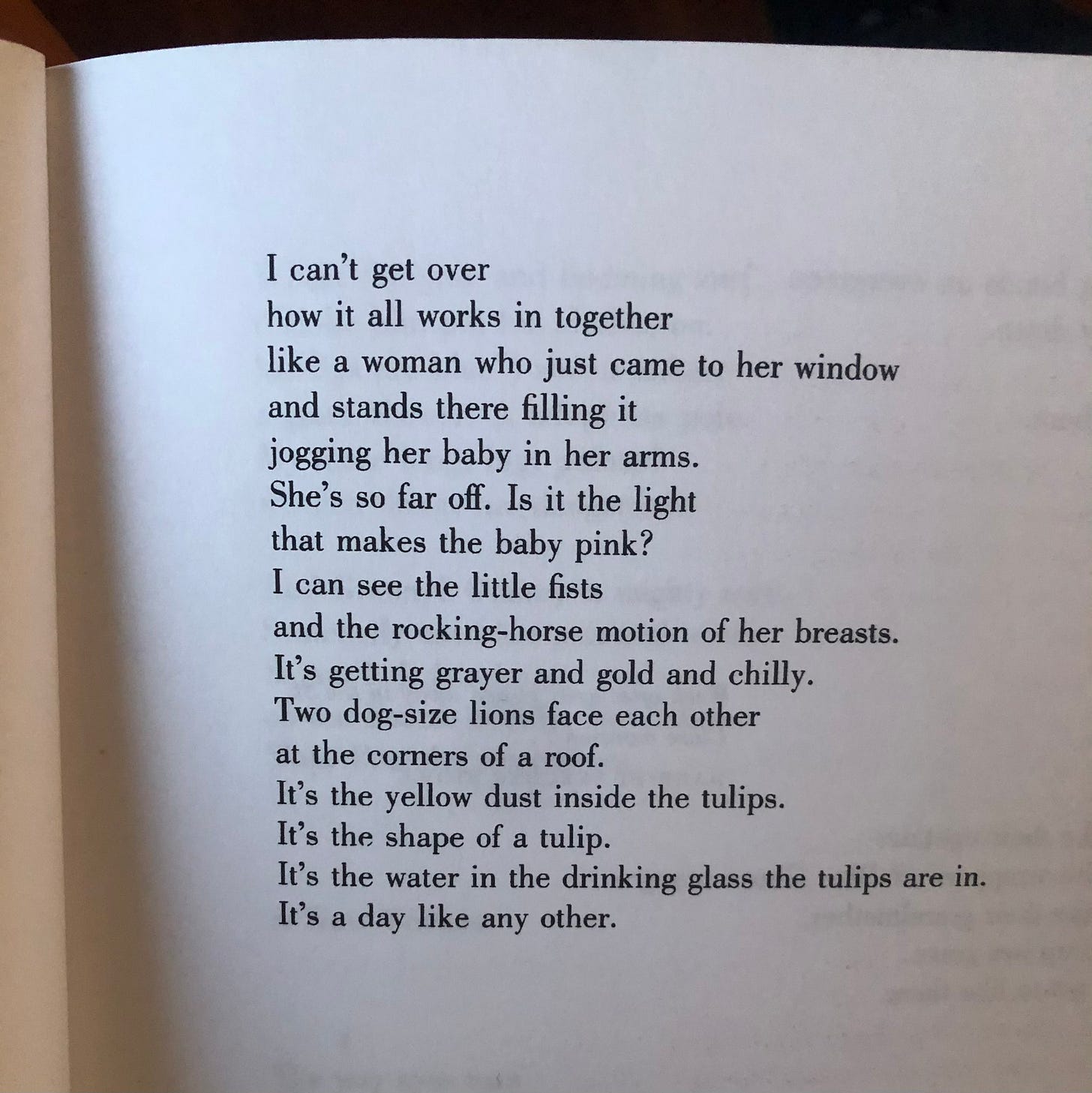

Here’s the poem as it looks in my edition of Schuyler’s Collected Poems (FSG, 1993).

I love this poem so much, and, as with other Schuyler poems, as I say towards the end of the episode, I’ve long had trouble saying why. I have attempted to explain my love once before, for what it’s worth, in this essay. Part of my interest in Schuyler has to do with the feeling he gives me, as I read or listen to him, of merely being with him—and in a way that’s less to do with what a poem seems to be about than it is with something harder to put my finger on, something to do with quality of attention, tone of voice, feeling of embodiment. The feeling of contact.

We talk about some of that in the episode, but Eric has offered another way of understanding why Schuyler might be a poet to love:

Poetry is always trying to describe what feeling is like, what reality is like. It’s really the least gussied-up, sophisticated way to talk about poetry, and I think Schuyler is celebrated rightly for two reasons that go into that: one, he does seem to really convey, in a kind of just-rightness for those that enjoy his poetry, what a thing is like, and that could get kind of philosophical and out of hand and hard to pin down, but then he’s always also indicating what it is, things as they are. And it’s the play of those two things, one that seems super literal and just kind of pointing to it, indicating that the world is there, that it is, that we should attend to it, and the other, evoking what it’s like.

This tendency towards indication as part of what poetry can do—“not meaning but our being here,” as Eric describes it towards the end of the episode—is an idea that Eric is developing from his mentor (also a teacher of mine), Paul Fry, who describes something he calls the “ostensive moment” in literature as the “indicative gesture toward reality which precedes and underlies the construction of meaning” (A Defense of Poetry, 13). It’s a tendency that directs the final four lines of “February,” in which Schuyler again and again tries to point to what it is in the day that has captured his attention. Not a question of what the day means, but more like what it’s like to be in the day. Description is just right and also beside the point. I hear the “it’s, it’s, it’s, it’s” of those four lines more than I keep what they point to. The tulips in the poem are really in the poem, and nowhere else, but what’s odd and beautiful is that as we read the poem they’re right in front of us, too, in the dying light at the end of winter, as the light returns.

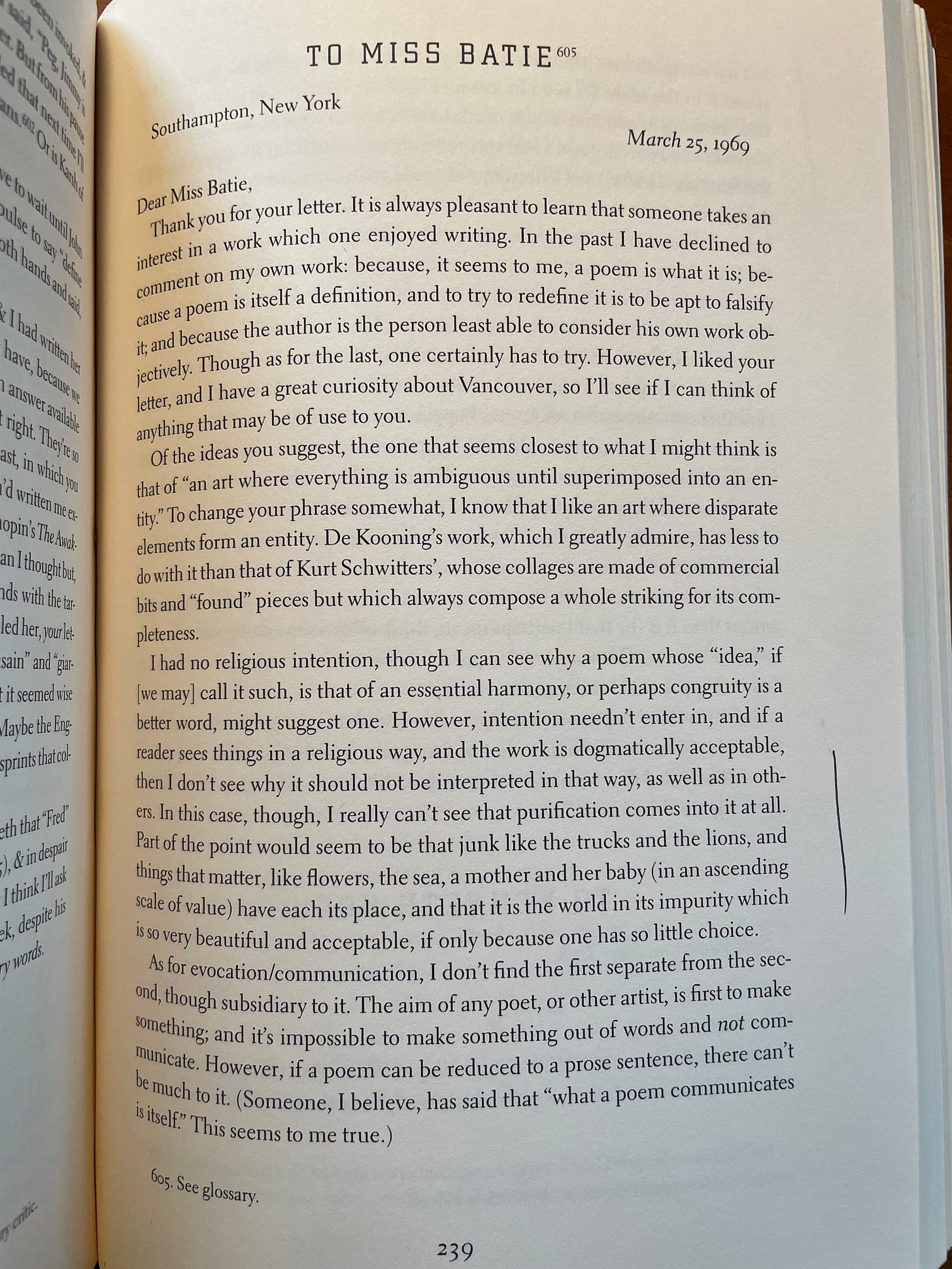

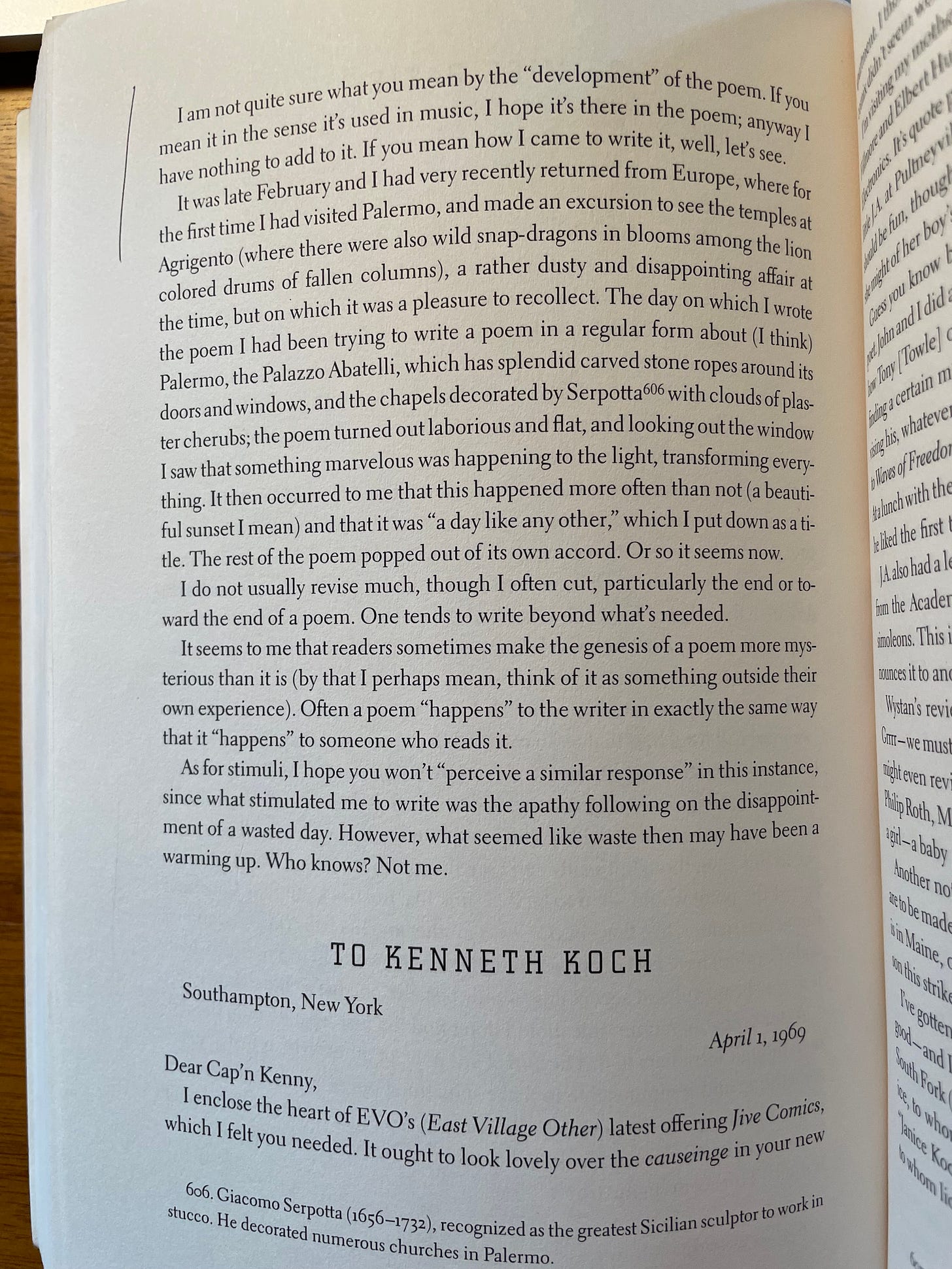

Schuyler himself might have been skeptical of this kind of theoretical or philosophical discussion, but I think he had his own way of describing what Eric and I were after. Here’s the full text of a letter that Schuyler wrote (but apparently never sent—the letter was found, unsigned, in John Ashbery’s papers) to a woman who wrote to him to ask about the poem.

It’s a marvelous letter.

The last thing I want to say—I’m typing this up right now a few minutes before 5 p.m. on the day before March first, and the dumb literalist in me wants to hit send right at the hour—is that I hope you’ll hear in this conversation how the love between two friends might be like the love of a poem, and how, in attending to a poem, perhaps especially if you’re doing so with someone you love, you get to be in the room the poem makes.

Finally, a few links to things that come up in our discussion:

Andrew Epstein’s blog post on “February.”

The PennSound archive of Schuyler recordings, including the recording we listen to in the episode.

Paul Fry’s A Defense of Poetry, where he discusses the “ostensive moment.”

Eric refers at one point to Wallace Stevens’s phrase “the basic slate, the universal hue.” That phrase comes from “Le Monocle de Mon Oncle.”

Eric Lindstrom is Professor of English at the University of Vermont and the author of two books: Romantic Fiat: Demystification and Enchantment in Lyric Poetry (Palgrave, 2011) and Jane Austen and Other Minds: Ordinary Language Philosophy in Literary Fiction (Cambridge UP, 2022). He's also the guest editor of two collections of essays: Stanley Cavell and the Event of Romanticism (Romantic Circles, 2014) and Ostensive Moments and the Romantic Arts: Essays in Honor of Paul Fry (Essays in Romanticism, forthcoming in March 2023). His essays have appeared in such journals as ELH, Studies in Romanticism, Criticism, Modern Philology, and Modernism/modernity. His most recent article, “Promethean Ethics and Nineteenth-Century Ecologies,” published and available open access at Literature Compass online, was co-written with Kira Braham. Eric is completing a third book, James Schuyler and the Poetics of Attention: Romanticism Inside Out, and, from the gleanings of that project, assembling an uncreative, marginally scholarly commonplace called “‘Now and Then’: A Poetics and Commonplace of Intermittence.” You should check out his own Substack, beginning with this post collecting his work on Schuyler, and follow him on Twitter (where he has the good sense to be less active than me).

Once again, you can listen to our conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. Please follow the podcast, and consider leaving a rating or review if you’re enjoying it. Share an episode with a friend! Here’s to March.

I'm interested in the work "Europe" or the "Old World" does in this poem, as a memory to be overcome (through deflationary and at times anti-intellectual means, like the purposefully unsophisticated sea/see/sea rhyme, or the fleeting and instantly negated image of the trucks flying into the air) but as one that nevertheless persists -- like perhaps in the incongruous, anti-Pieta image of motherhood and the pink baby at the end.